Belgian comics

I'm organizing this page based on the following video introducing the current design of the Belgian passport, which prominently features Belgian comic characters.

The page numbers will be noted in the headers of the comics, but you won't really lose any relevant content if the video becomes unavailable or you are otherwise unable to watch it. I've liberally linked to the Lambiek Comiclopedia, which is more knowledgeable than I can ever be — and all for free! So I'll just stick to basic facts and my own opinions on this page.

The featured comics

Tintin (0,2,6-7,35)

Tintin is what I consider to be the quintessential adventuring comic, comparable to the adventure-oriented Scrooge McDuck comics by Carl Barks.

After some growing pains with its first few albums, which were naive at best and hopelessly racist at worst, Hergé began deepening out his stories, both through more intricate plotting and actual research into the places his characters visited. The result? A rich tapestry of engaging adventures in timeless settings. Their best cinematic comparison would be Indiana Jones (which of course didn’t escape the notice of Spielberg, leading to him directing a Tintin movie).

All 23 official albums should be readily available in English, as well as an officially endorsed incomplete version of the 24th album. I wouldn't bother with the first two albums, but if you are a completionist, there is also a bit more Tintin out there to discover. There's a ‘movie album’ of Tintin and the Lake of Sharks that got an official release, which features comic-specific art on top of backgrounds from the movie. A pirate version exists with more regular backgrounds, which feels less janky. There are also unauthorized completed versions of the 24th album, the most famous drawn by French-Canadian artist Yves Rodier, who also produced other pastiches.

As for animated adaptations, there are two I would highly recommend as a visual representation of the comics. There are two beautiful movies by Belvision from the late 60s and early 70s, one which is a not always faithful adaptation of The Seven Crystal Balls and Prisoners of the Sun, the other which is an original story (the aforementioned Lake of Sharks). Then there is the generally more faithful 90s TV adaptation by Nelvana. Belvision also made its own TV adaptation in the early 60s, but the limited resources make it a rough watch.

Natacha (5)

A comic by François Walthéry I've never really read, and certainly not as well-known as other examples. It's about the adventures of a young stewardess. I assume it was chosen to increase the female representation in the selection, but I'm not sure if a character written by a man to be explicitly sexy was the ideal choice.

Marsupilami (8-9, 25)

This character spun off from Franquin's Spirou. Marsupilami is the titular character and species of animal.

An animated adaptation by Disney was a segment of Raw Toonage, a 1992 animated show. It's a rather unfaithful adaptation, but one I remember fondly nonetheless. Because of legal issues and other shenanigans stemming from Disney's Eisner years (the company's best and worst), it's unlikely that this series will ever resurface legally.

Spike & Suzy (10-11)

All previous comics in this list were originally francophone, but here we have the first Dutch one. It centers around the adventures of the titular main characters and their family. While they go on a lot of adventures like Tintin, there's more comedy, fantasy and even science-fiction elements in play. This was probably my favorite as a kid, even more so than Tintin, though the quality tends to vary.

It's a long-running series that's still actively being published. The first albums of the mainline red series (named after the color of its covers) were rather rough around the edges, with a folksy charm to it. But for publication in the prestigious Tintin magazine, creator Willy Vandersteen was challenged to refine his art and his plotting. The result of this is the so-called blue series, named so because they were later published as albums with blue covers. He adopted the clear line of Hergé, redesigned the characters and produced what fans consider to be his finest stories. While the red series would eventually continue and characters would revert to their more iconic designs, the clear line was kept.

These comics have sporadically appeared in English under various names. Bob and Bobette (after their French name), Spike and Suzy, Luke and Lucy, and Willy and Wanda. In any case, each print run only covered a small selection of these comics. It'll be tough to get a proper grasp of the comics in that manner. Even so, other exports did fare better, and thus this is probably the only Flemish comic that got really popular outside of Flanders.

There was at some point a live action movie adaptation of one of the album, but it's very forgettable. I only remember it because I got to go to its premiere for free, which was pretty fun! A 3D animated movie adaptation is equally non-noteworthy, to be honest, but it did receive an English localization under the Luke and Lucy moniker.

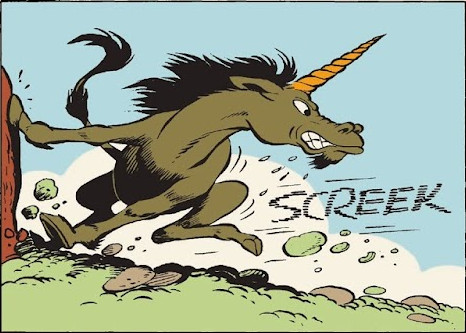

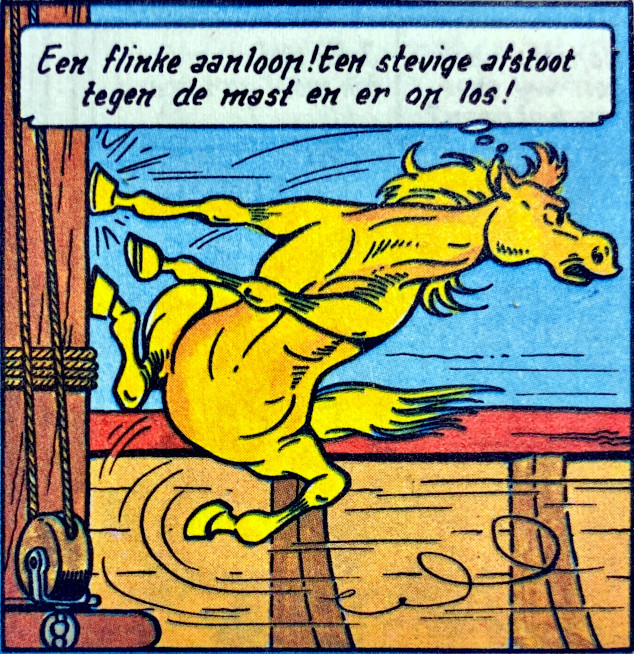

There is one interesting tidbit that ties him further into the topics of this website. As shown by a Dutch Spike & Suzy podcast, Vandersteen let himself be heavily inspired by a Carl Barks unicorn when drawing horses in a specific pose, specifically Sleipnir and a golden horse.

Kari Lente (14-15)

Way more obscure than Natacha, presumably chosen for the same reason (and being from the other side of the language border). Another comic, this time by Bob Mau, that I never actually read. Notably, the style and overall tone of this series is very inspired by Franquin.

Blake & Mortimer (16-17)

My father jokes about hating these comics by Edgar P. Jacobs with a passion! Why, you ask? There's too much text!

First appearing in the Tintin magazine, and using the clear line style of the comic the magazine was named after, Blake & Mortimer aims to be a more serious thriller with a healthy dose of pulp, but very light on humor.

The Kiekeboes (18-19)

A Flemish family comic by Merho in the tradition of Spike & Suzy and Jommeke, but of a later generation, which is perhaps best exemplified with daughter Fanny, who quickly became the star of the comic. She's yet another sexy independent woman who often serves as fan service, but is precisely why I don't care strongly for this comic.

Lucky Luke (20-21)

A Marcinelle School cowboy comic by Morris, who was from Flanders but mostly published in French. From 1955 onwards, the comics were mainly written by Frenchman René Goscinny, better known for Astérix, until his death.

The Smurfs (22-23,32)

This spin-off from Peyo's Johan & Peewit is probably the only Marcinelle school comic I actually regularly read as a kid. They're perhaps better known today for their iconic Hannah-Barbera animated series, or the rather questionable live-action movie adaptations. Before the American animated series, there's a neat Belvision movie based on their introductory Johan & Peewit album, localized in English as The Smurfs and the Magic Flute.

One particular piece of merchandise I fondly remember is figurines produced by Schleich and Bully, with accompanying Smurf houses to put them in. There were also various edu-games published by the infamous Infogrames, which I played a lot.

Spirou (24-25)

First appearing in the eponymous magazine, this elevator operator was notable owned by publisher Dupuis from fairly early on and was often passed around. His French creator is virtually forgotten, and a lot of the series' defining aspects got introduced by Jijé. Jijé then passed on the series to a young André Franquin in 1946. Under Franquin the series expanded from gags to full-fledged adventures, and fans generally consider it to be Franquin's series.

Jommeke (26-27)

Jommeke by Jef Nys was originally a gag comic published in the Flemish catholic parish weekly, and later various (originally catholic) newspapers. The series quickly expanded to full albums with adventures, though I've always seen them as a bit more juvenile and safe than, for example, Spike and Suzy. That's also part of the charm, however.

Largo Winch (28-29)

A series I have little experience with. It's a more mature comic with a realistic art style, very much aimed at adults. To my understanding it's about business intrigue?

Nero (30-31)

Another major Flemish comic, this time by Marc Sleen. It's a family comic that differentiates itself by adding absurdism and strong satire into the mix. Sleen generally worked alone, and the more loose and off-model drawing style that resulted from this actually inspired many irreverent comedic comic artists of later generations.

Beyond the passport: what else is out there?

Celebrity and tie-in comics

I'm glad these aren't featured! Two of these are actually some of the best-selling series in Flanders these days. F.C. De Kampioenen is a series based on a public TV sitcom which I don't think very highly of, and the same goes for the comic. The other is Urbanus, a fictional version of a popular comedian, and a comic notorious for its raunchy and irreverent humor (which I don't care for either).

For a time, pretty much every popular local series or celebrity had its own comic series, but most never lasted for long.

The Red Knight

Vandersteen made many comic book series outside of Spike & Suzy, but this is one I'd like to highlight in particular.

Originally starting as a straightforward medieval-based series with light supernatural elements here and there, successor Karel Biddeloo gradually introduced sword and sorcery elements and even science fiction and a dash of the erotic into the mix. A far cry from the rather conservative Vandersteen! Under Biddeloo, for better or for worse, the Red Knight had essentially become pulp. After his death, the series went back to knightly adventures while selectively incorporating Biddeloo's more fantastical elements, a balance which I really enjoyed.

Fascination with America

The passport already featured cowboy Lucky Luke, but Belgian comic artists were often rather fascinated with the United States. There's The Bluecoats (Salvérius), a Marcinelle school comic about two Union soldiers during the civil war, and the Belgian-French Western production Blueberry, drawn by French artist Jean Giraud (Mœbius). Herman's Jeremiah is set in a post-apocalyptic United States.

Sometimes the US is featured through a detour, like Vandersteen's adaptation of Karl May's stories about Native Americans. Or in the case of Jommeke, through its association with Flemish country singer Bobbejaan Schoepen and his amusement park Bobbejaanland.

What's all that about schools?

Throughout this article, I've mentioned the Marcinelle school a few times. Basically, older Belgian comics tend to be divided in three schools:

- The Brussels school or Clear Line is the style associated with Hergé's Tintin. It is defined by strong colors and lines, and a lack of hatching. It's classic, refined, though to some maybe a bit boring and predictable.

- The School of Marcinelle was the style pioneered by Jijé, Franquin, Morris and Will. Compared to the Clear Line, it's looser and always in movement. Marcinelle is where the headquarters of publisher Dupuis is located. International audiences will probably primarily know the style from The Smurfs.

- The Flemish school is a bit of a hodge-podge following Vandersteen. It's essentially the Clear Line, but more folksy and prone to caricatures.